Moon illusions

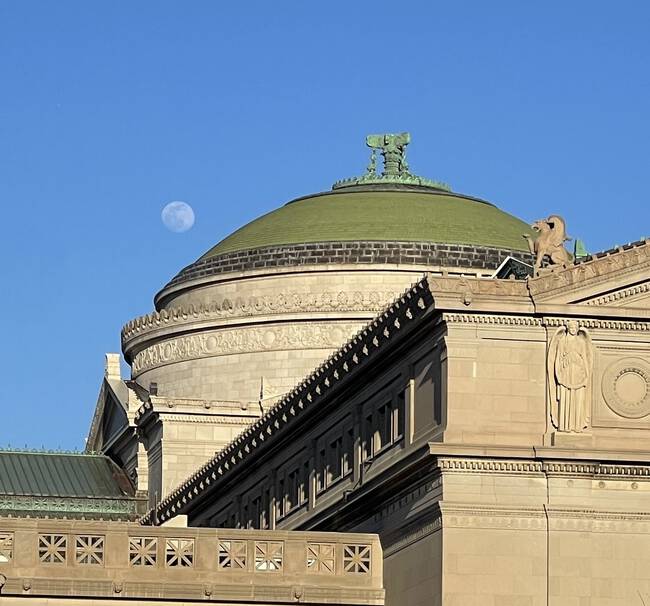

The moon, rising in the early evening, just above the rotunda at the Museum of Science and Industry. When I took this picture it was short of a full moon by a day or two:

There’s a long-standing puzzle about the moon when it is near the horizon: why does it look bigger? This is usually just called the “moon illusion.” The problem has so far not been definitively resolved by any modern scientific explanation, leaving it open to speculation by philosophers, amateurs, and polymaths. Also, not all people perceive the illusion in the same way. For example, I have seen the moon on the horizon that looked huge, but I didn’t find this to be true when it was next to the rotunda in this picture. Subjectively, it looked “normal-sized.” I believe this comes through in the photograph. But a quick image search for apparently large moons does show many near the horizon, or a surface-level object, that do look huge (the fact that this illusion–or the lack of it–can be carried through into photographs is a property worth noting–not all illusions do).

Optical illusions involving forced perspective take one or more objects and place them near a reference object, which deceives the intuition for size and space. There is usually something deceptive about the presentation of the reference, making the original seem smaller or larger by comparison. Maybe the moon’s appearance is another example of forced perspective. This illusion has been noticed for so long that the competing paradigms to explain it are well-established:

These include both the “apparent distance” theory

…the brain perceives the Moon when near the horizon to be farther away than an elevated Moon. Therefore, the brain calculates that the horizon Moon must have a larger angular or linear size (about 1.3 to 1.5 times larger) than when viewing the Moon when it is higher in the sky.

And the “apparent size” theory:

…when the Moon is low and close to familiar objects, such as houses, trees, and mountains, we already know or quickly estimate their apparent size and distance, then the brain incorrectly calculates the angular size of the Moon compared to the familiar objects on the horizon. When the Moon is elevated, there are no earthly objects to compare it to, so the brain perceives as being more distant and therefore, smaller than the horizon Moon.

Both explanations are from Robert Garfinkle’s lavishly comprehensive recent book on the moon, Luna Cognita (section 6.11.4, “The Moon Illusion”).

It seems to me like these solutions are trying to account for the moon’s paradoxical aspect when viewed in the traditional way: with the naked eye. Although the moon is the largest object in the sky, and it moves across the horizon each day or night, it never really changes size. The combination of motion and fixity of apparent size–this is not a normal property of most physical phenomena. Movement on the earthly plane is usually associated with some change in size. Also, to my knowledge, the moon is also the only object in the sky that that possesses both regular motion and any apparent size at all. We speak of brightness of the stars and planets, but they all appear to be points of light, closer to mathematical locations on a plane than three-dimensional objects. So the trouble arises with this object, the moon, that moves yet is not subject to growth or reduction, and which follows predictable, calculable cycles like the stars, yet retains the obvious imperfections of substance and matter (shape, texture, depth). It is not surprising that the mind/brain does not know how to treat it, and is tricked into applying standards of growth and change which the moon, in its own very strange class of objects, refuses.

Sources

Robert Garfinkle, Luna Cognita: A Comprehensive Observer’s Handbook of the Known Moon. Springer, 2020.